The Woman Who Was Too Radical for History

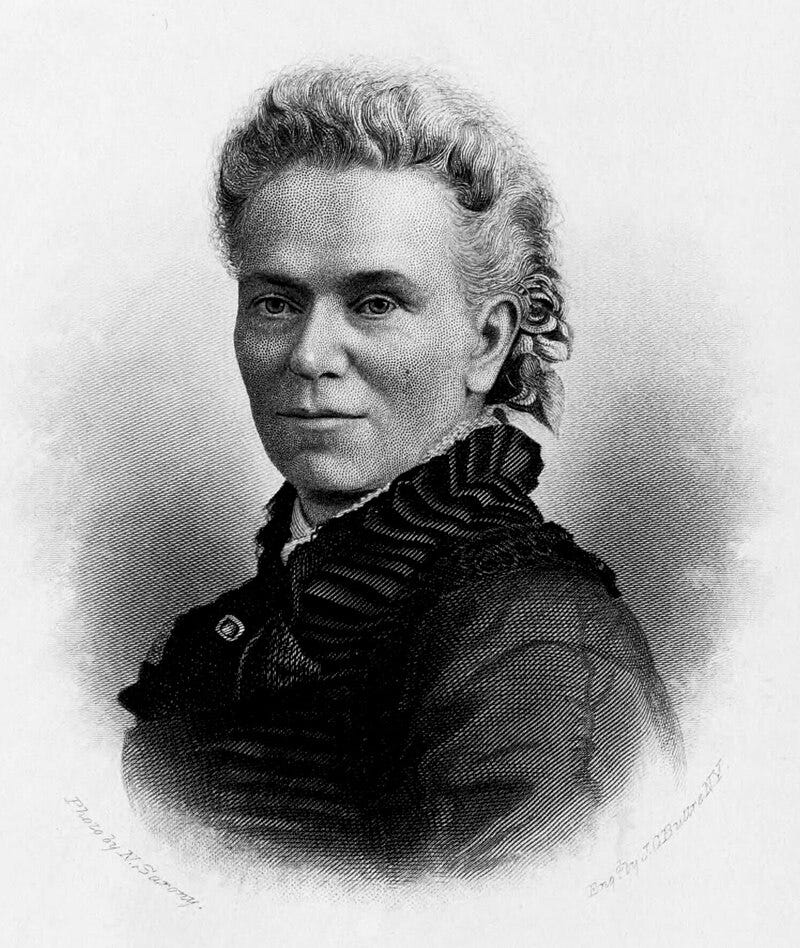

For World Book Day and Women's History Month, it's time to connect with the legacy of Matilda Joslyn Gage.

Hello and happy Thursday to you!

Today is World Book Day AND Women’s History Month, so I need to tell you about a book called Woman, Church and State by Matilda Joslyn Gage because I’m gonna hazard a wild guess that you never got the memo.

Gage was once called “the woman who was ahead of the women who were ahead of their time.” High praise, indeed. She was born in New York in 1826 and – fun fact – was also L. Frank Baum’s mother-in-law. Yes, the man who wrote The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.

Last year, I wrote a detailed biography of Gage and her impact for the wonderful New Herstoria project, which you can read here. Otherwise, I’m going to summarise her life because it’s the book’s impact that I want us to focus on.

A Glimpse into Gage's Life:

Matilda Joslyn Gage was born into a middle-class family in New York. Educated at home, her father – a prominent abolitionist – personally oversaw her education. In 1845, she did what all good middle-class ladies ought to do and married Henry Gage, a merchant. They went on to have five children.

But Gage was never going to give her life to domesticity, and her husband was hella supportive of her various activist endeavours. These included:

A petition stating that she would willingly spend six months in prison and pay a substantial fine for breaking the Fugitive Slave Act. Remember, this was some years before the abolition of enslavement, so any people who escaped their enslavers in the South could be forcibly returned. It’s unclear how many formerly enslaved people Gage and her husband harboured in their home before the passing of the 13th Amendment (which made enslavement illegal).

In 1852, she gave her first public speech at the third National Women’s Rights Convention in Syracuse. This propelled her onto the main stage of the women’s suffrage movement.

Gage co-founded the National Woman Suffrage Association in 1869, as well as the New York State Woman Suffrage Association. She served as president of the latter for nine years.

Woman, Church and State

If you ask me, the chef’s kiss of her work was the publication of Woman, Church and State in 1893. In this book, Gage argued that the Christian Church systematically oppressed women, a process that began with the eradication of ancient matriarchies. She also referred to the European Witch Trials as a ‘holocaust’ against women. You can read the book for free here, and I really encourage you to connect with Gage, even if you don’t agree with her arguments. (Her stats are definitely problematic, if you ask me, but it’s the fire in her belly and the impact that we want to soak up).

As middle-class femininity was so heavily bound up with notions of Christian morality and duty, you can imagine the reaction Woman, Church and State drew. Gage was immediately shunned by her suffrage sisters, and the NAWSA – an organisation she had co-founded – vehemently rejected the book.

In the longer term, all of Gage’s works were also shunned and rejected, including one of the most important works in women’s history (if you ask me) – her essay ‘Woman As An Inventor.’ Published in 1883, this essay recovered dozens of women scientists and inventors whose contributions to human civilisation had been deliberately written out of history, claimed by men, or simply forgotten over the centuries.

It wasn’t until the late 20th century that Gage’s works were rediscovered by feminist historians. In turn, this led to Gage becoming the eponym for the Matilda Effect – the systemic bias against acknowledging the contributions of women to STEM. And, oh, the irony … that Gage would herself become a victim of the effect she had worked so hard to overcome.

Why I Admire Gage

I often get asked which women from history I admire the most. It’s a tough call to make, but Gage is usually the first woman I think of. Probably that’s because she was both a doer and a maker of history. She contributed so much to women’s activism in the 19th century, especially for suffrage, but (unknowingly) laid the groundwork for the discipline that would become women’s history. She was able to highlight the various problems that historians of women’s history encounter, even before we had something to study. It’s for these reasons that no other woman hits like Matilda Joslyn Gage.

If you missed it, you can read the in-depth bio of Matilda that I wrote here.

And I’d love to hear of any women’s history books that have inspired and educated you, too. Just hit reply.

Until next time,

Kaye x

https://substack.com/@johnshane1/note/c-98951363

I very much enjoyed this piece as I am embarrassed to say I had never heard about the activism of Matilda Gage. I can agree that she has to be close to the helm of extraordinary women. I think Mary Wollstonecraft is still at the top for me with the publication of The Vindication of the Rights of Women in 1792 and her other writings and her extraordinary life in general.