Why We Need to Reclaim

Plus, the most outrageous case of writing a woman out of history that I have EVER seen. (And you know it takes a lot to shock me).

Hello to you!

You may have noticed that the title of my new book is ‘Reclaimed.’ All the books that will follow in this series (yes, it’s a series 😍) have the same title.

Why, though? What does it mean to reclaim?

Let’s start by affirming that we don’t do fluffy, Hallmark, girl power history over here. Basically, that’s woman-washing on steroids, and it can go and dive head-first into the Atlantic. Of course, that’s not to say that there is something inherently wrong or bad about feeling inspired or motivated by women’s history. It’s normal to be inspired by stories. It's also normal to seek out inspiration. Humans are creative beings with minds that are wired for storytelling. Arguably, there’s something suss if stories don’t inspire you. And, to quote one of the greatest women who ever lived*:

“We define what our goals are and what we think is possible to reach by the stories we inherit about the people who came before us."

But there’s a fine line here, dear reader. People from the past do not exist to validate your existence. Or mine.

Reclamation goes beyond inspiration and validation. Firstly, it’s about acknowledging that women and girls have never had their voices heard or their perspectives considered in the same way that men have. They’ve always been several steps down the ladder. History, therefore, is not neutral. It is a power structure in itself.

Secondly, it’s about excavation. I quote the statistic from Dr Bettany Hughes a lot, that women account for only 0.5% of recorded history. How accurate that is, I couldn’t say, but my experiences of doing women’s history tell me that even if that number is accurate, we have barely dipped our toes into the ocean of that world. I’m serious. What is common knowledge about women from the past is probably less than 0.5% of that 0.5%.

I am still dredging up brand-new things. Just me. Consider how many researchers of women’s history are active around the world right now, each digging up something we never knew we never knew. This is why continuous research and critique of existing bodies of knowledge are so important. There is still a lot to uncover because you cannot reclaim what you do not know.

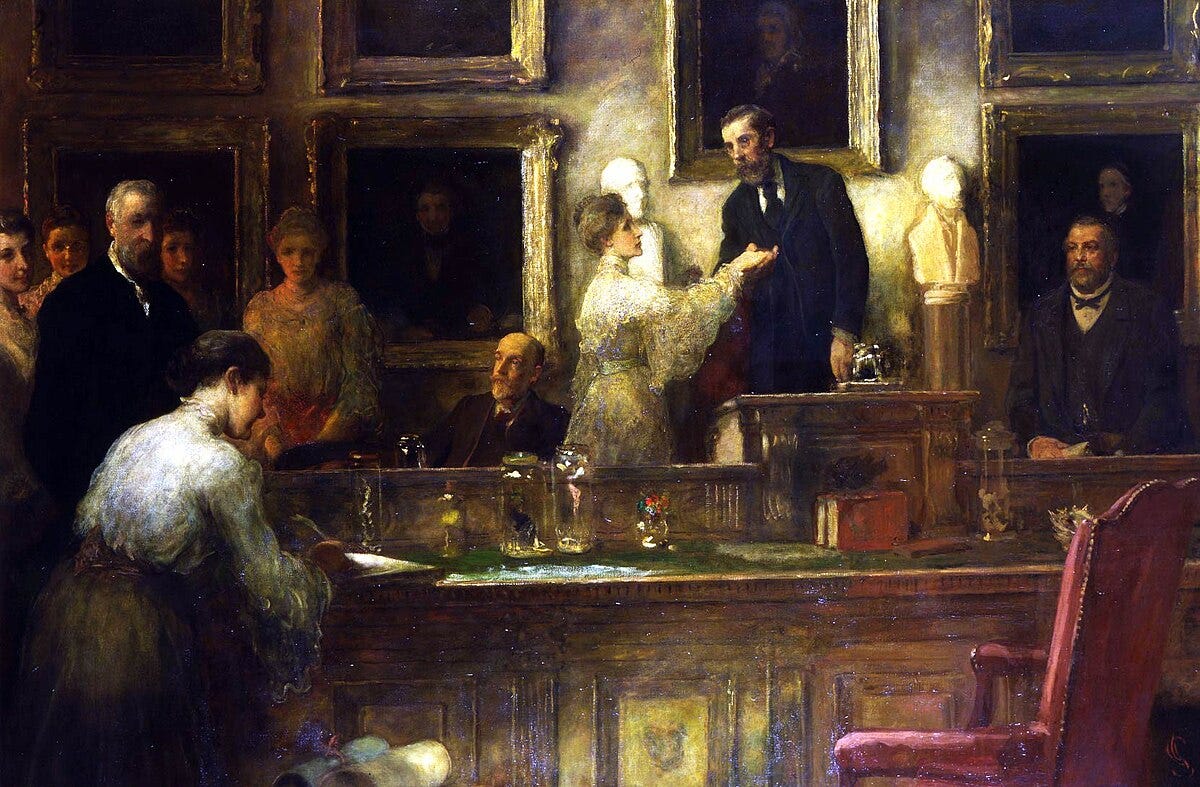

On the topic of dredging up, while I was working on my book last week, I found probably the most outrageous example of a woman scientist being written out of history. Her name was Mary Ann Stebbings. She was a botanist and botanical illustrator who, in 1904, became one of the first female fellows of the Linnean Society. Props, indeed. The next year, a portrait was commissioned to celebrate this milestone in the society’s history. Here is the portrait. You can see Mary in the right centre:

The portrait was later ‘edited,’ shall we say. And take a look at who is missing …

I’ll be spilling all the T on Mary’s story in my new book, but, seriously, is that not the most outrageous example you’ve EVER seen?! We should all be raging on her behalf.

Anyway, back to reclamation …

The third part is integration. What should we do with all this ‘new’ knowledge about women?

Arguably, integration happens on several levels. There is personal integration. Once women (and men) realise that women have played significant roles in the construction and maintenance of civilisation, their sense of self will inevitably change.

This might sound a bit out there, but I know this from my own experience. Like many, many people, I once believed that women’s history was a long story of victimisation and oppression, with the odd bit of heroism and ‘despite-the-odds’ thrown in. It doesn’t help that history education constantly reinforces this downtrodden and compensatory narrative of women’s collective past. Also, women as exceptional. Can we just stop this now, please? Before I stick a pencil into my eyes.

Anyway, once I (deliberately) forgot everything I’d been taught and headed off down the beaten track, I uncovered a very different narrative. And you cannot come back from that journey with the same mindset and the same ideas. It’s not possible.

After personal integration comes collective integration. When we truly know women’s legacy, how will we move forward as a collective? Because hear me when I say this: things will not stay the same. For example, how can our society have a stubborn gender gap in STEM when we understand how the gap came to be and, more importantly, what is still propping it up? The short answer is that it can’t. Throwing money and awareness at it will no longer make sense. The gap itself won’t make sense. Things will shift.

(As an aside, this is what we’re seeing now with the male loneliness epidemic and the increase in female celibacy. Women now have more choices than they have EVER had in recorded history, even when we consider the pushback against some of those rights. They can earn their own money, open their own bank accounts, buy their own houses, have legal protections, educate themselves and consume whatever they like. They are also largely accountable to nobody, including - and this is crucial - a male relative. Is it really any surprise that women are choosing themselves after generations of fighting for the right to make choices over their lives? No, dear reader, it isn’t. Yet, I’m baffled that more people aren’t seeing that these ‘trends’ are the culmination of something much, much older).

So, I feel like ‘reclamation’ is a fitting way to describe my work going forward. My goal has never been to hype up women and hate on historical men, but to present a well-rounded, accurate view of our past because, no, that does not exist right now. This is also about critiquing the systems we have inherited so that we don’t drag them into the future. Because, yes, we do have a choice.

You’re still here so I know you feel the same. What a great time to do some reclamation.

Until next time,

Kaye x

*That’ll be Gerda Lerner, obvs.

Just the erasure from the painting was enough to grind my teeth. Who removed it and why?

What an interesting story. Per your comment that "Women now have more choices than they have EVER had in recorded history, even when we consider the pushback against some of those rights. They can earn their own money, open their own bank accounts, buy their own houses, have legal protections, educate themselves and consume whatever they like," I think of this as part of a larger concentric circle.

This trend first occurred in the 1830s and up to the Civil War in America when women refused to marry, prefering to stay single, often setting up households with other women (friends, sisters, other relatives). They saw how in marriage, men took women's money, drank to excess, often abused them, and controlled their every move. At a time when motherhood was considered the ultimate and only role for women, defying society's strict norms was an incredible act of personal defiance.

The only problem was, jobs for women were very limited. But it was also start of the university movement for women, which would only take another 200 years, but what the heck. We got there. Kind of.